New orders for manufactured durable goods rose to $289.65B in July, the highest level since November. This represents a 9.9% increase from the previous month and better than the expected 4.0% growth. The series is up 1.3% year-over-year (YoY).

New orders for manufactured durable goods in July, up five of the last six months, increased $26.1 billion or 9.9 percent to $289.6 billion, the U.S. Census Bureau announced today. This followed a 6.9 percent June decrease. Excluding transportation, new orders decreased 0.2 percent. Excluding defense, new orders increased 10.4 percent. Transportation equipment, up two of the last three months, drove the increase, $26.4 billion or 34.8 percent to $102.2 billion.

Durable Goods

Durable goods refer to tangible products that can be stored or inventoried and that have an average life of at least three years. Durable goods are typically expensive and therefore tend to be purchased when there is confidence in the economy. New orders for durable goods are a leading indicator, meaning when purchases increase it typically hints at an improvement to the economy. On the flip side, when the new orders trend down, it is indicating a lack of confidence in the economy.

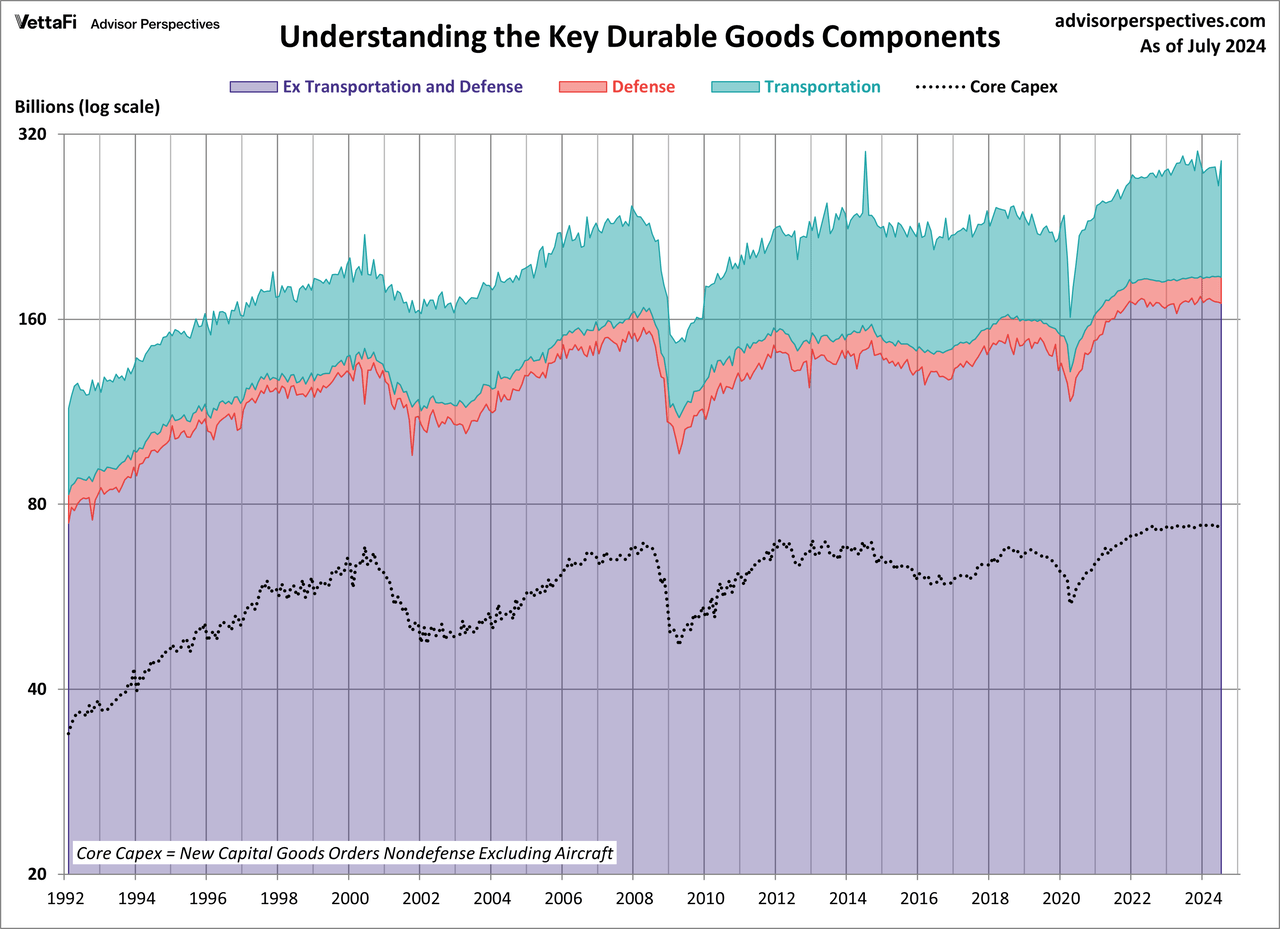

Economists frequently study this indicator excluding transportation or defense or both. Just how big are these two subcomponents? Here is a stacked area chart to illustrate the relative sizes over time based on the nominal data. We’ve also included a dotted line to show the relative size of the core capex subset, which we’ll illustrate in more detail below.

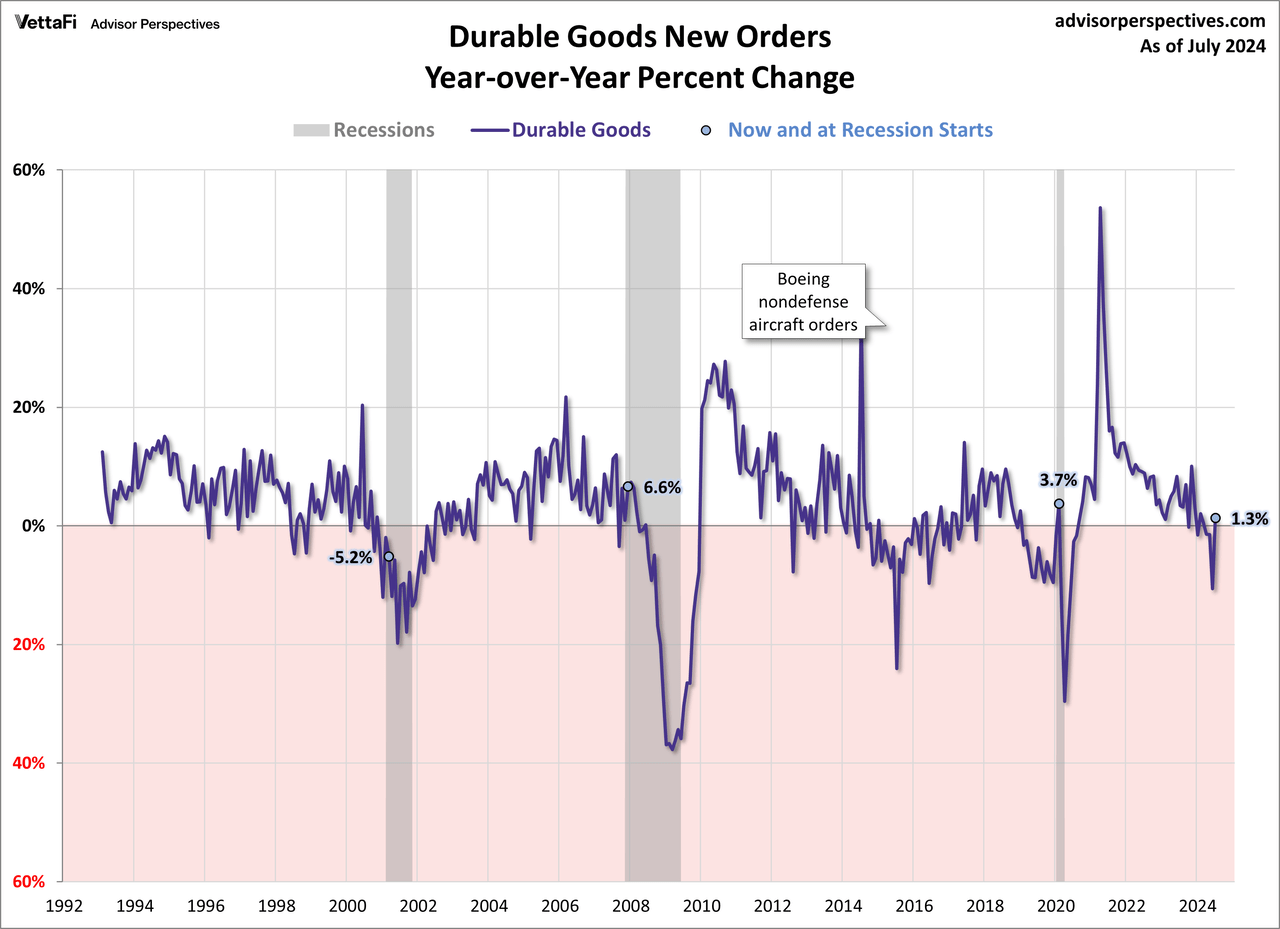

The next chart shows the year-over-year percent change in durable goods. We’ve highlighted the value at recession starts and the latest value for this metric.

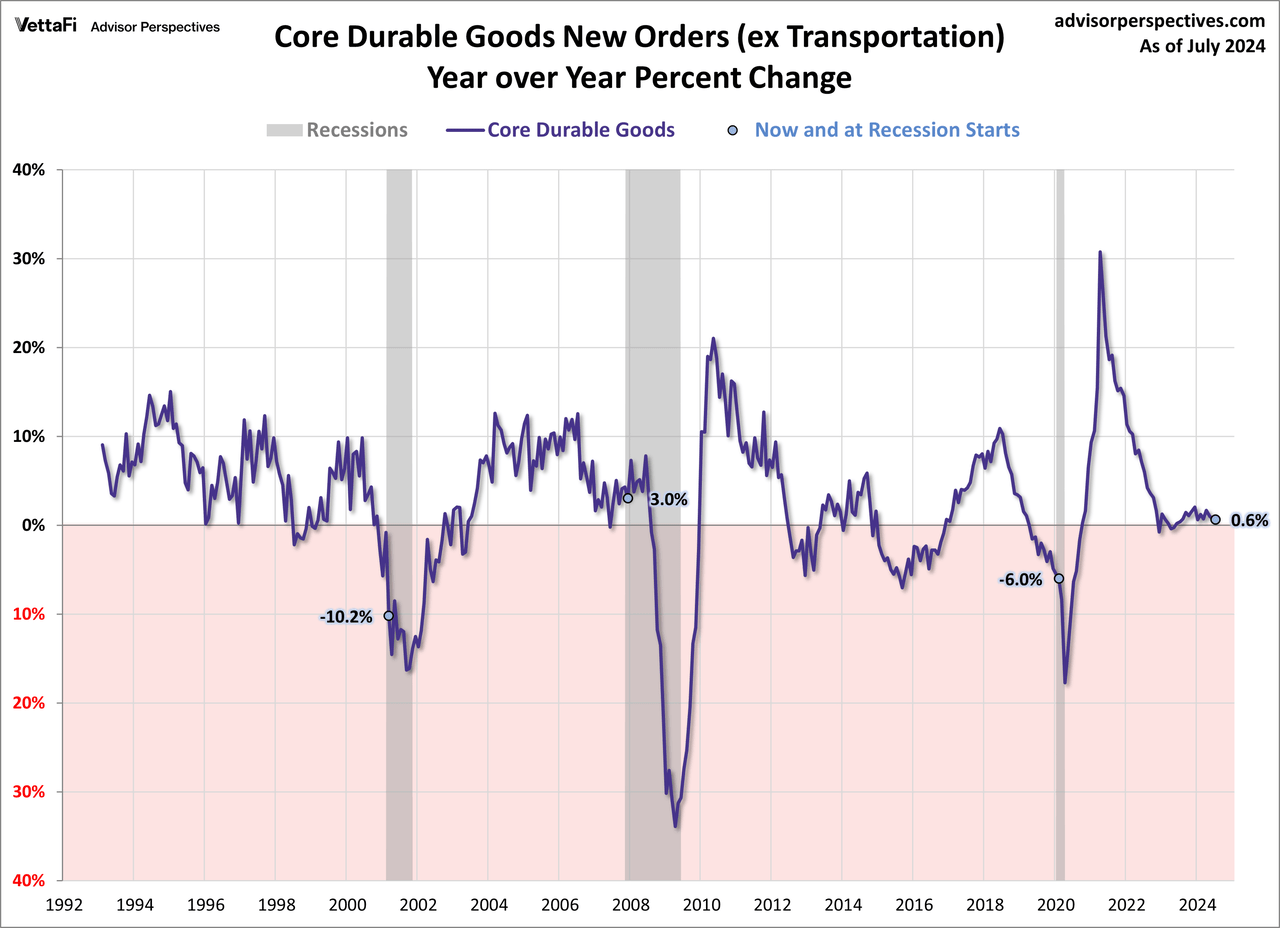

If we exclude transportation, “core” durable goods were down 0.2% from the previous month, lower than the expected flat growth. Core durable goods are up 0.6% from one year ago. The next chart shows the year-over-year percent change in core durable goods.

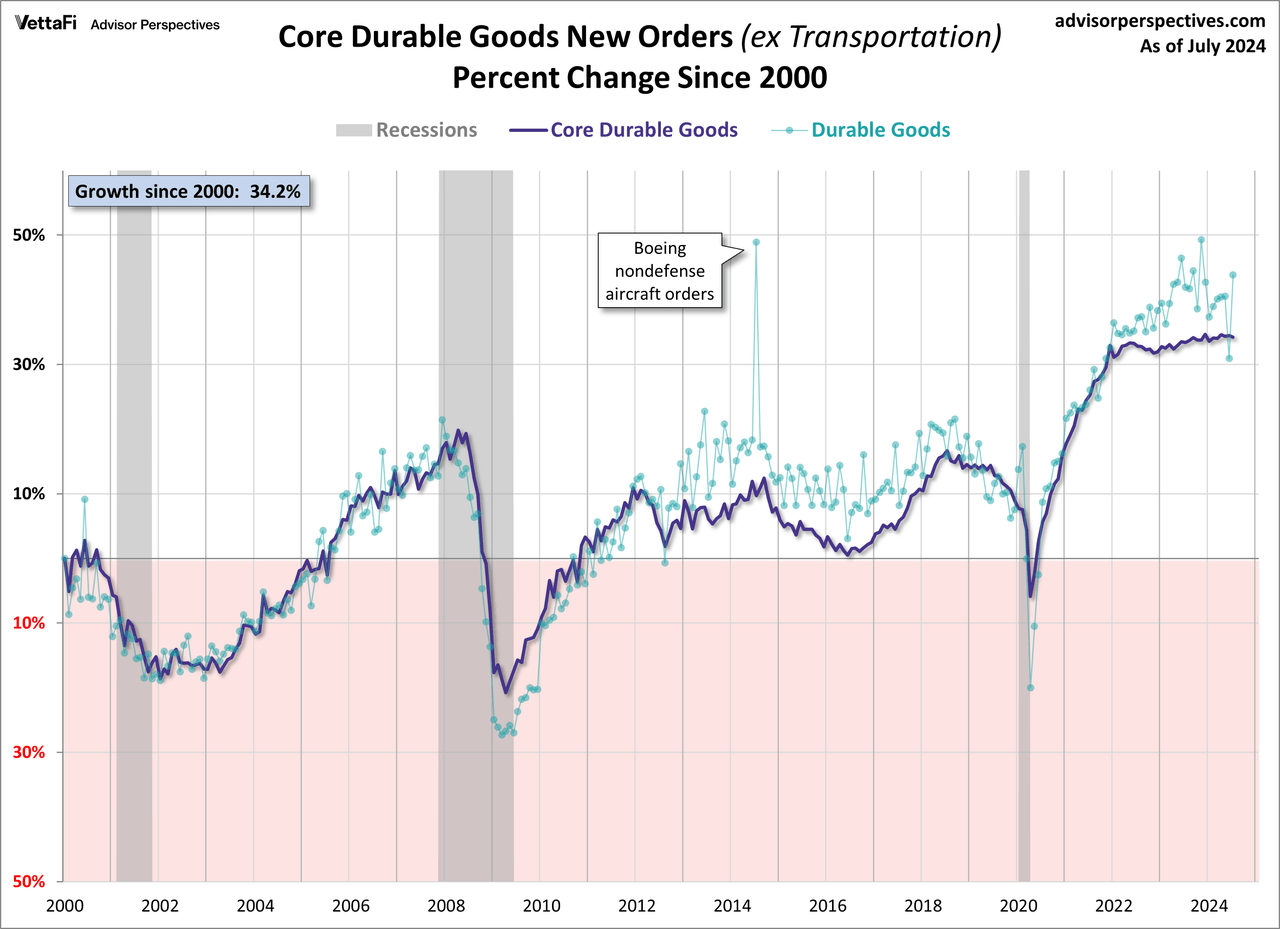

The next chart shows the growth in core durable goods (purple line) overlaid on the headline number (green dots) since the turn of the century. This overlay helps us see the substantial volatility of the transportation component.

Since 2000, durable goods have grown 43.8% while core durable goods have grown 34.2%.

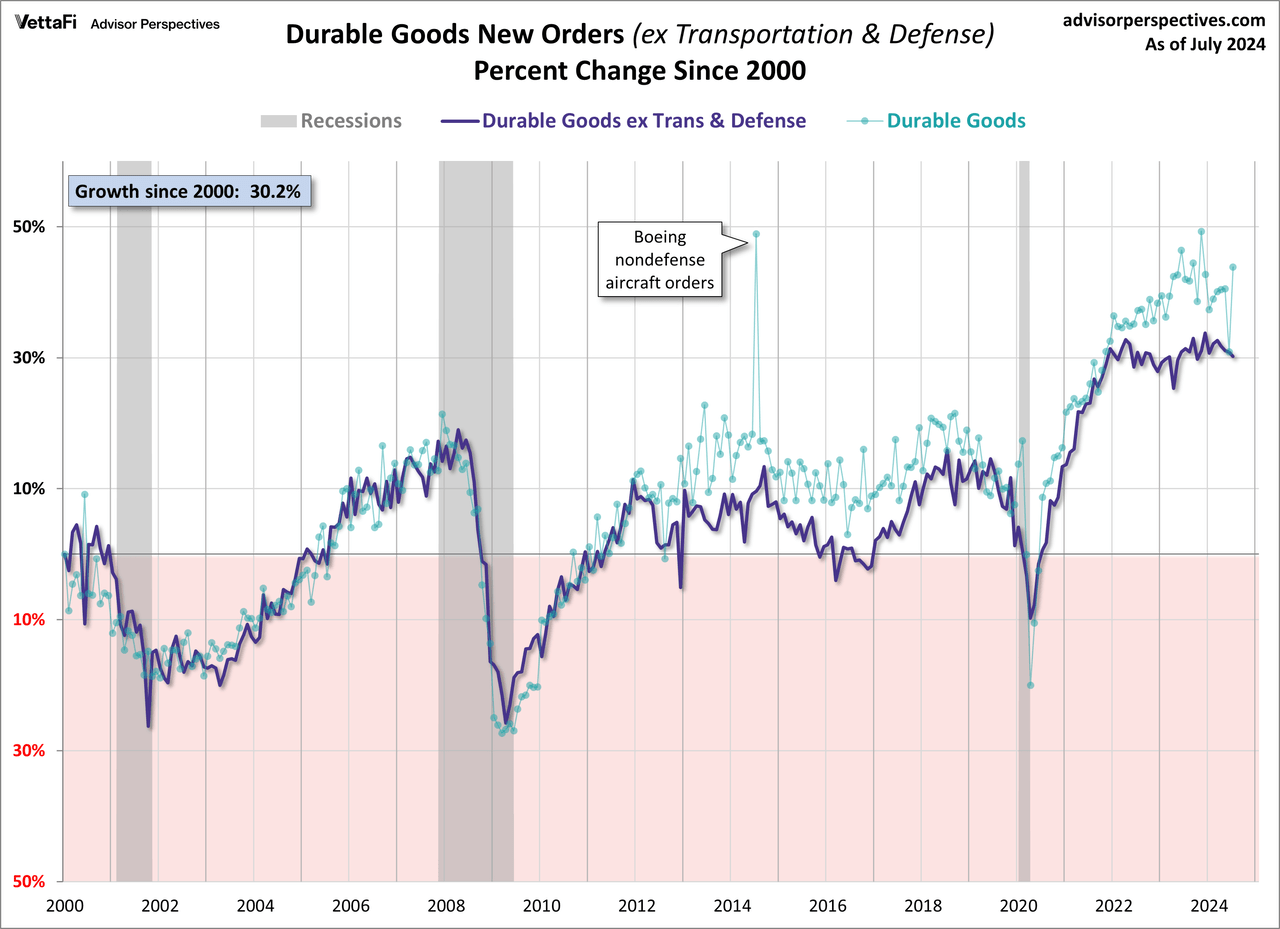

Here is a similar overlay, this time excluding defense as well as transportation (an even more “core” number). Since 2000, durable goods excluding transportation and defense has grown 30.2%.

Durable Goods – Core Capex

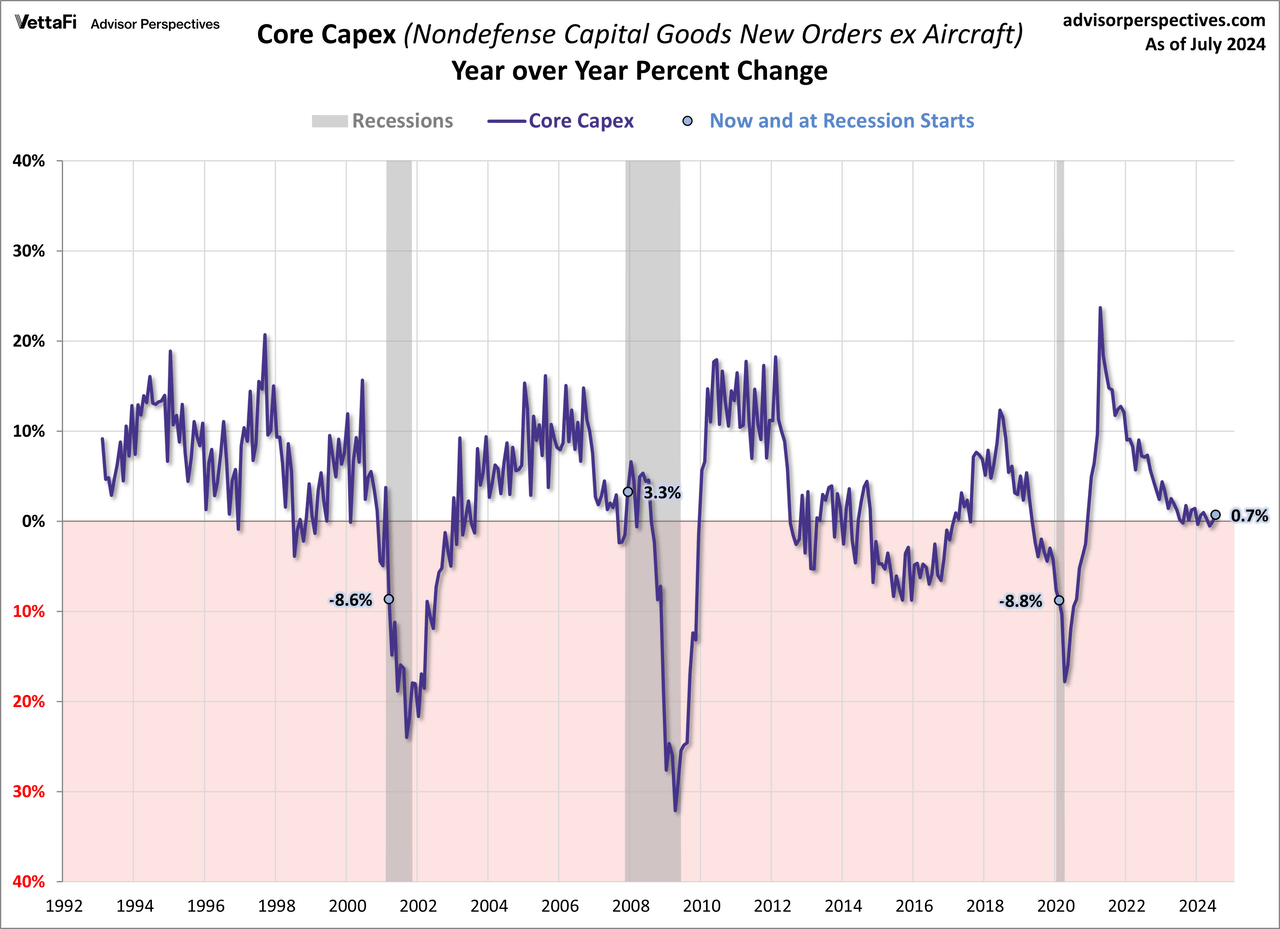

Core capital goods new orders are manufacturers’ new orders for non-defense capital goods excluding aircraft and is an important gauge of business spending, often referred to as “core capex.” Core capex is company spending that is used to acquire, upgrade, and maintain physical assets such as property, plants, buildings, technology, and equipment. This month, core capex was down 0.1% MoM and up 0.7% YoY.

The next two charts take a step back in the durable goods process to show illustrate core capex. Here is the year-over-year core capex.

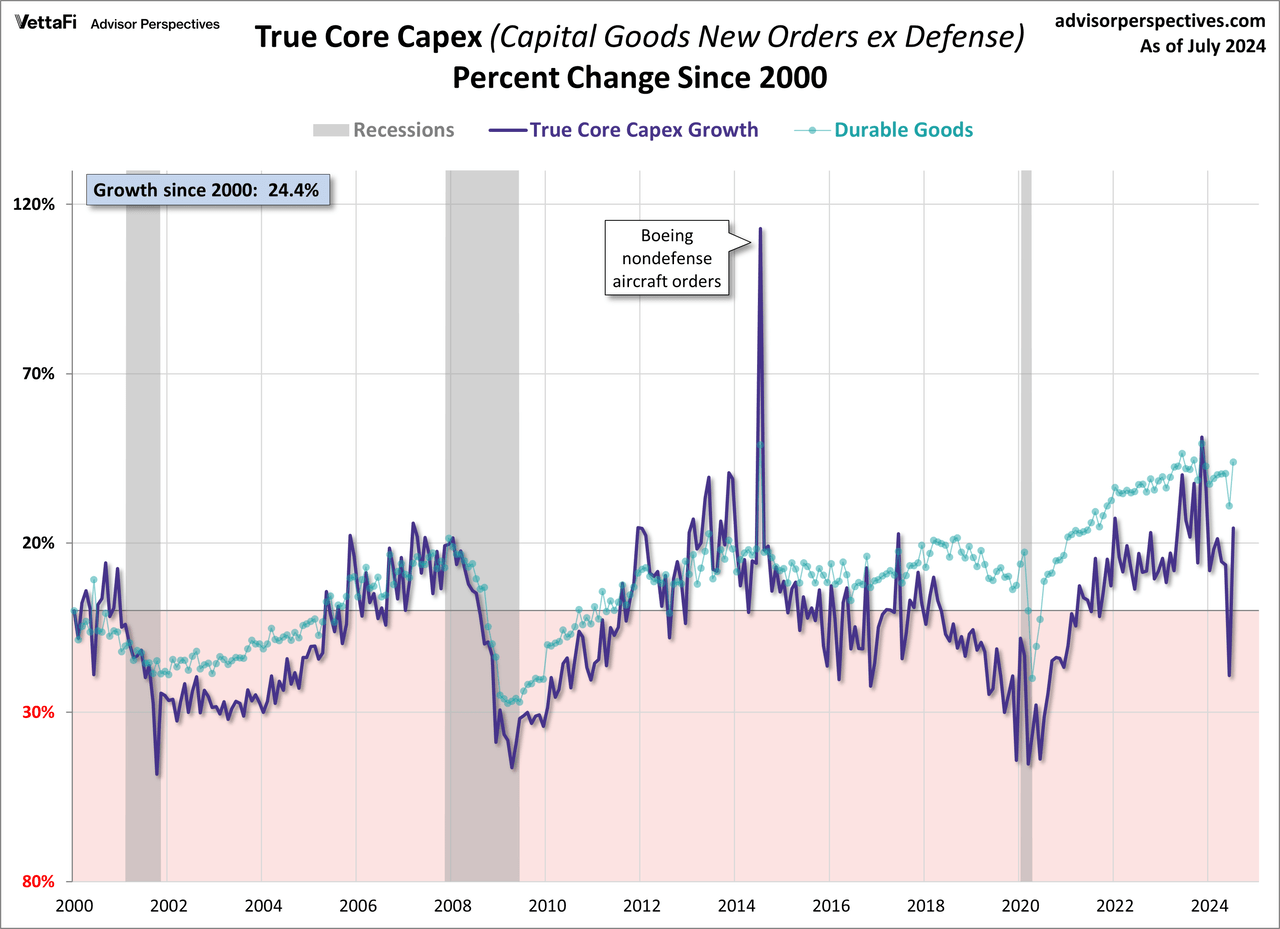

The next chart is an overlay of core capital goods (excluding defense) on the larger series, showing the percent change of the two since the turn of the century. Since 2000, durable goods have grown 43.8% while core capex has grown 15.1%.

The “Real” Durable Goods Data

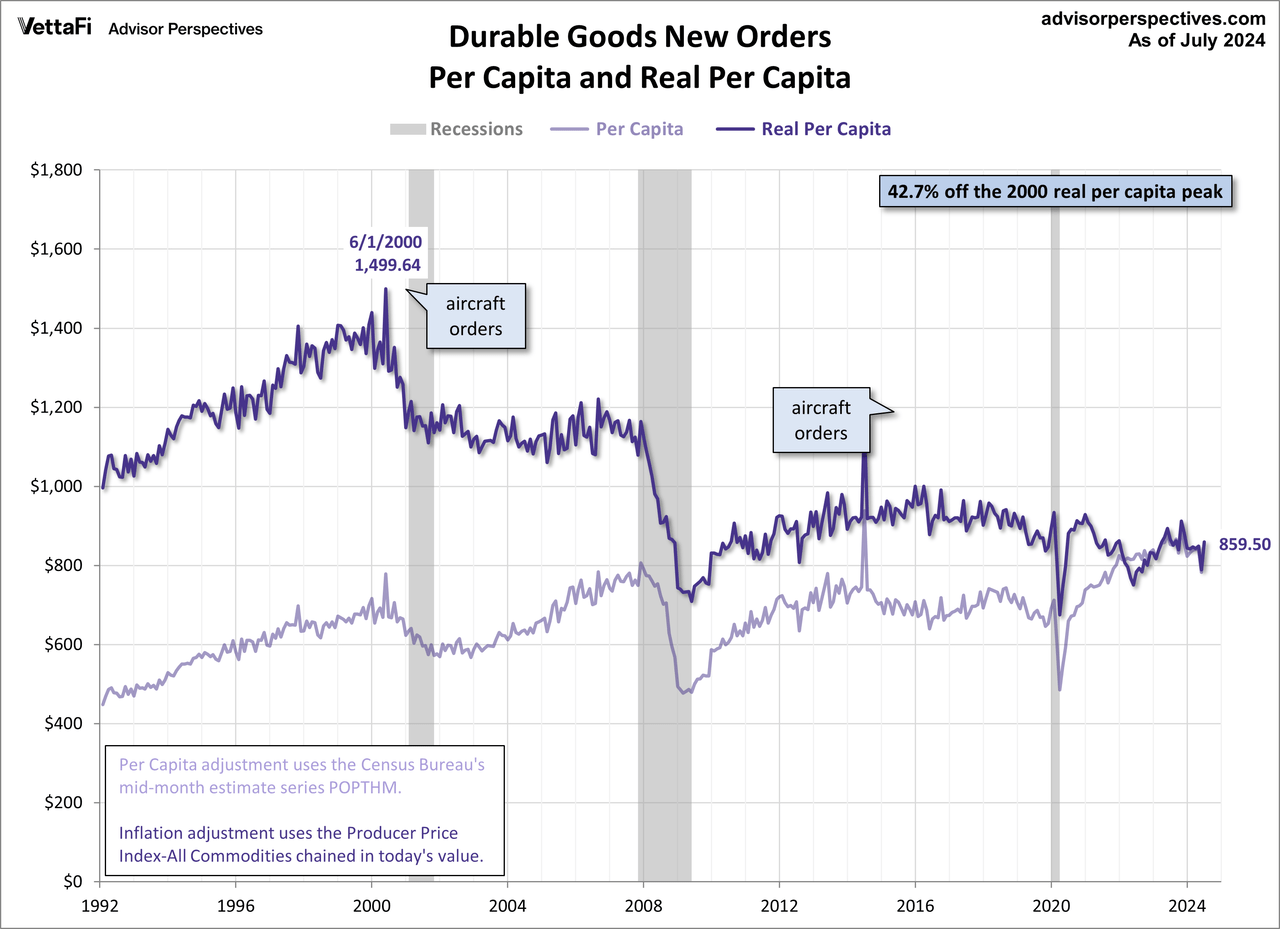

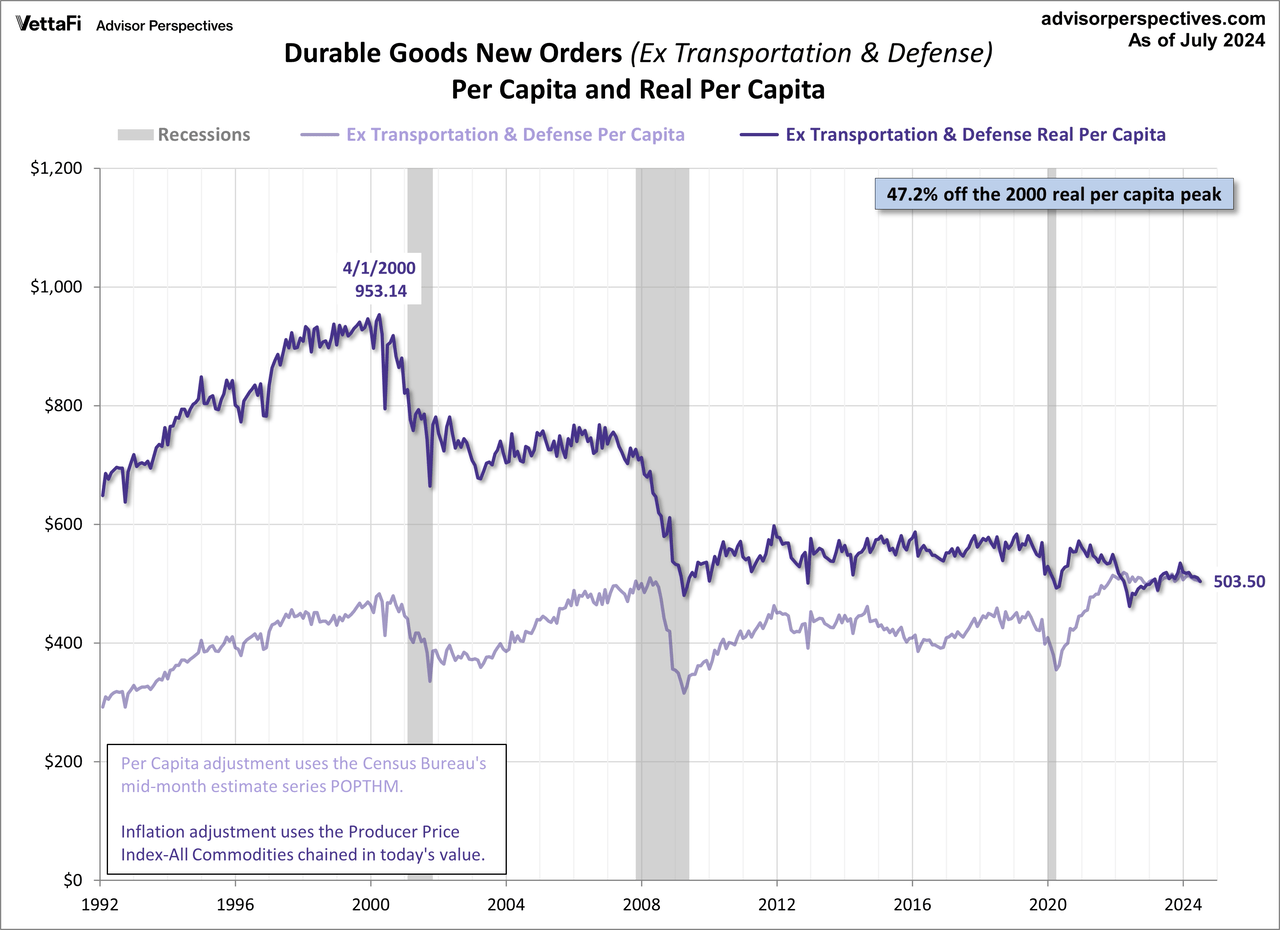

In theory, the durable goods orders series should be one of the more important indicators of the economy’s health. However, its volatility and susceptibility to major revisions suggest caution in taking the data for any particular month too seriously. Additionally, this series is not adjusted for either population growth or inflation. Let’s review the durable goods data with those two adjustments.

In the charts below, the lighter line shows the goods orders divided by the Census Bureau’s monthly population data, giving us durable goods orders per capita. The darker line goes a step further and adjusts for inflation based on the PPI for all commodities, chained in today’s dollar value. This gives us the “real” durable goods orders per capita and thus a more accurate historical context in which to evaluate the conventional reports on the nominal monthly data.

We’ve included a callout in the upper-right corner to document the decline of the latest month from the all-time peak for the series.

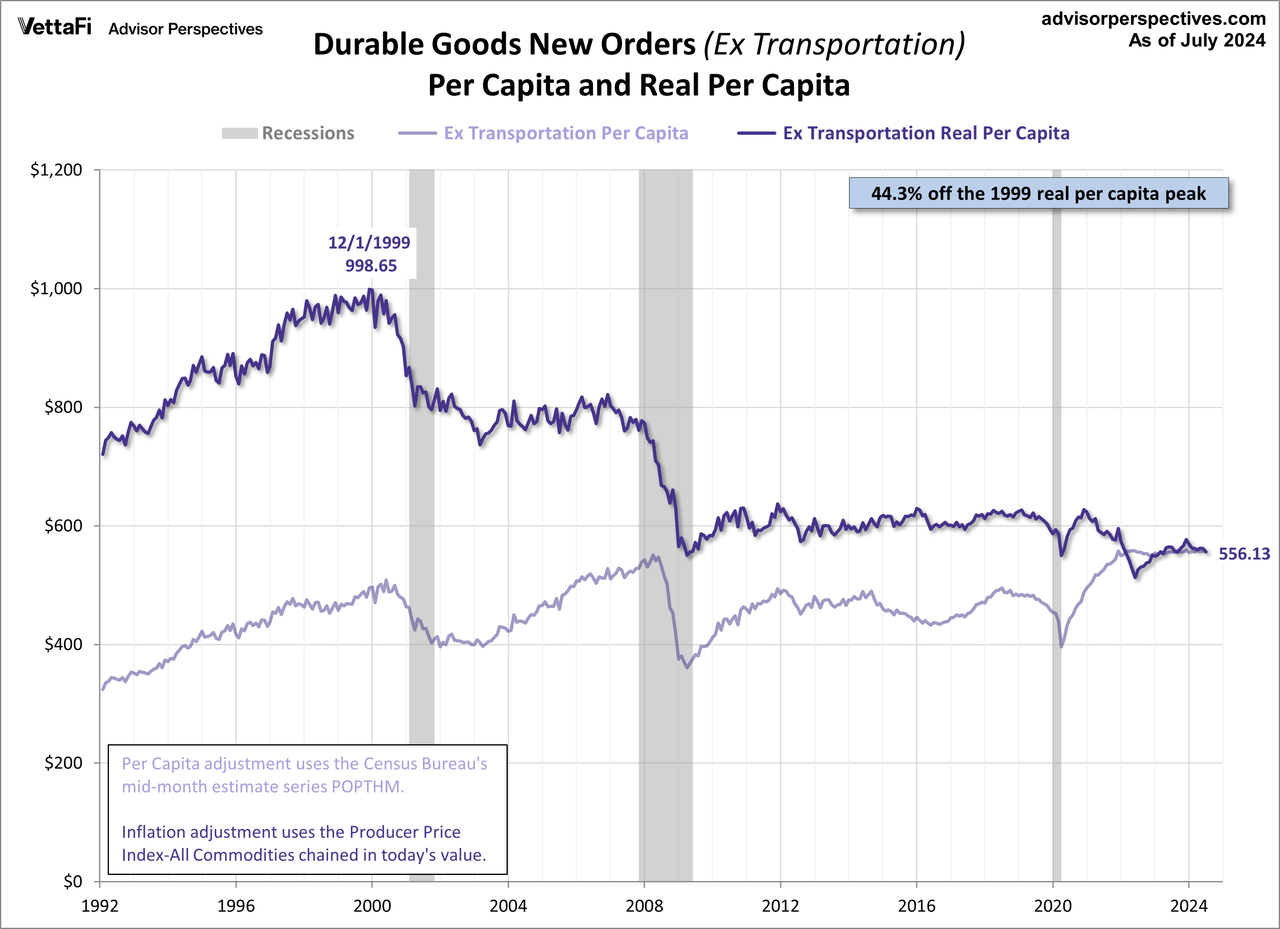

The next chart is similar to the first one except that it excludes the volatile transportation component, the series usually referred to as “core” durable goods.

Now we’ll exclude both transportation and defense for a better look at a more concentrated “core” durable goods orders.

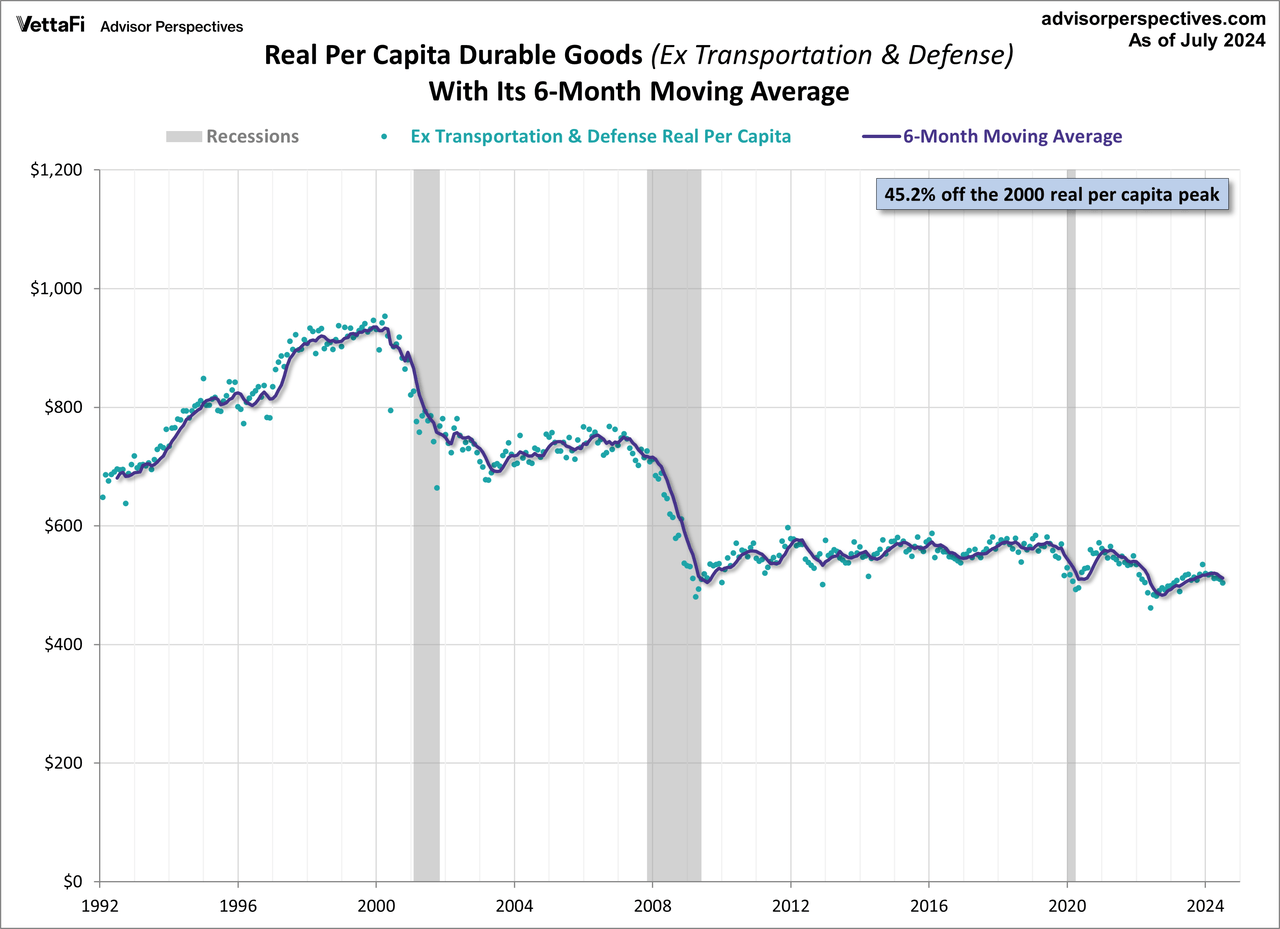

Here is the chart that gives the most accurate view of what consumer durable goods orders is telling us about the long-term economic trend. The six-month moving average of the real (inflation-adjusted) core series (ex-transportation and defense) per capita helps us filter out the noise of volatility to see the big picture.

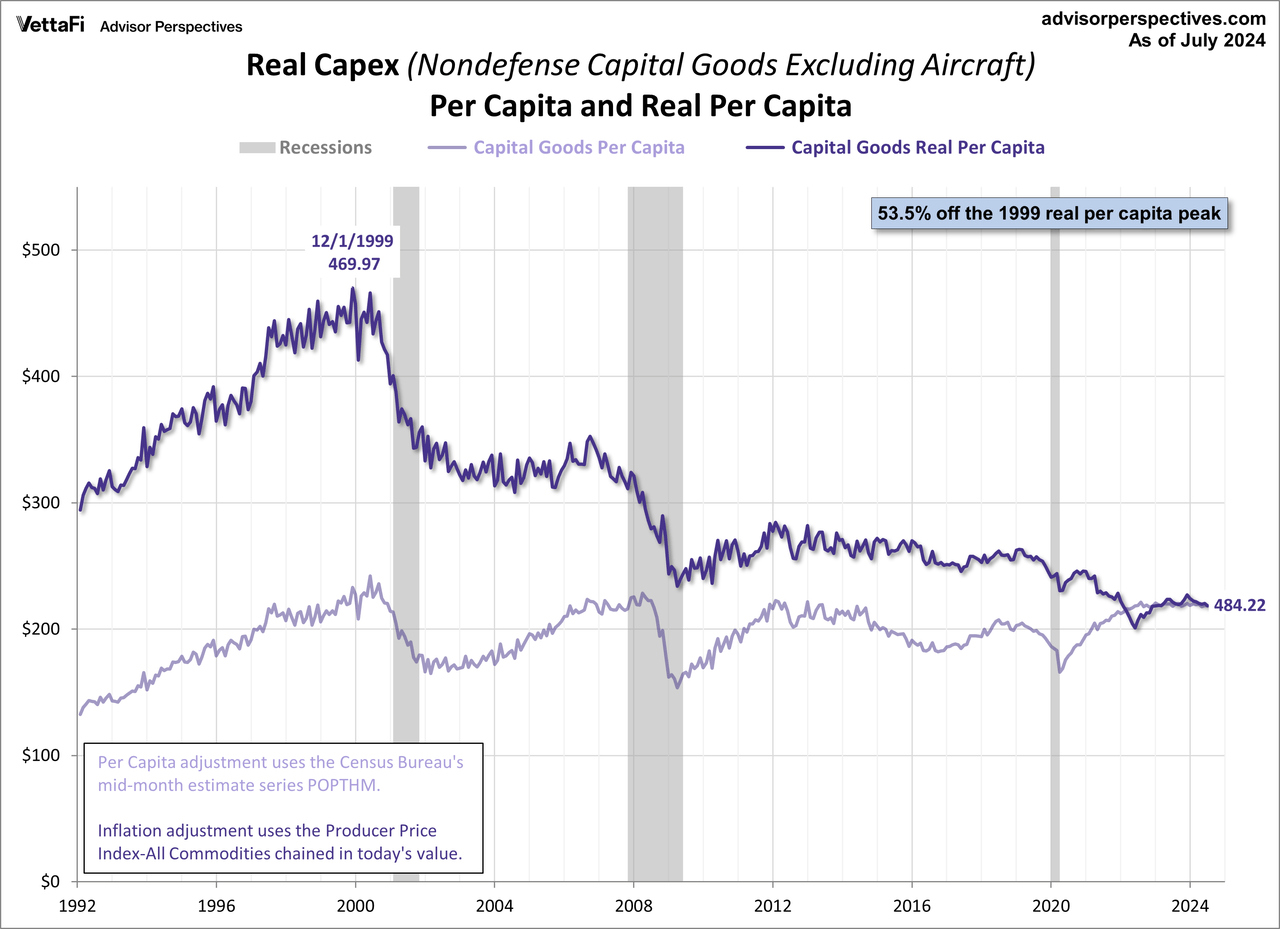

Durable Goods per Capita – Core Capex

Finally, let’s take a big step back in the sales chain and look at the popular series often referred to as “core capex” – nondefense capital goods new orders excluding aircraft (capital goods are durable goods used in the production of goods or services), shown here on a per-capita basis, nominal and real.

Here is the real per-capita core capex smoothed with its six-month moving average for a better sense of the trend. This metric has went nowhere for six years until the COVID recession, and then started to decline but has seen some growth in the recent months.

The Long-Term Trend in Durable Goods

As these charts illustrate, when we study durable goods orders in the larger context of population growth and also adjust for inflation, the data becomes a coincident macro-indicator of a major shift in demand within the U.S. economy. It correlates with a decline in real household incomes, as illustrated in our analysis of the most recent Census Bureau household income data:

- By Quintile and Top Five Percent

- Median Incomes by Age Bracket

The secular trend in durable goods orders also helps us understand the long-term trend in GDP illustrated elsewhere. See especially the most recent update on GDP.

As we can see from the various metrics above, revisions notwithstanding, the real per-capita demand for durable goods had increased since the trough at the end of the great recession. But new orders remain far below their respective peaks near the turn of the century. A key driver, or lack thereof, for healthy growth in durable goods orders is growth in household incomes.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here