By Robert Carnell, Carsten Brzeski, James Knightley

Risk of a China systemic banking crisis stemming from the property development company problems

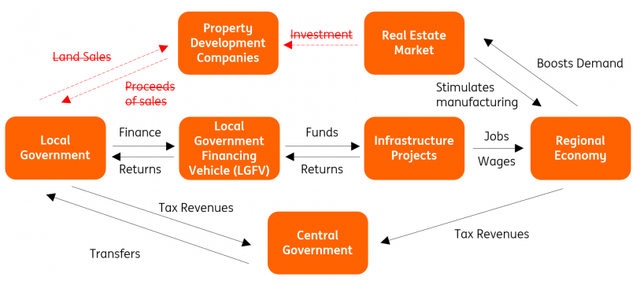

A lack of transparency and a convoluted financing system have raised fears that the problems of China’s property development companies and the spillover to local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) could result in banking failures. We think the risk of a systemic crisis is low.

LGFVs developed out of the limitations of tax revenue raising for local governments and have been a way for local governments to boost expenditure on infrastructure and invigorate the local economy.

Local governments are usually the sole or dominant shareholders of the LGFV, which issues debt that may be bought by banks and other financial institutions to pay for these projects – say, social housing or roads and bridges. The returns on these infrastructure projects are frequently insufficient to meet the debt service costs and repayment of loans, and so local government land sales to property development companies have traditionally made up the shortfall.

This process has led to a substantial build-up of LGFV debt and, in turn, bank exposure to such debt. The scale of LGFV debt is now about CNY 55 trillion, according to PIMCO estimates. Banks are on the hook for about 60% of that, which accounts for about 15% of total loans. Smaller regional banks are the most exposed.

Property market issues have reduced ability of local governments to sell land and fund LGFVs

ING

Clearly, the problems of the property sector cut this financing loop, raising the risk of LGFV default. However, while individual defaults cannot be ruled out – and some have already occurred – we consider the risks of a systemic banking crisis to be low. The central government and the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) are both committed to preventing a systemic crisis. The playbook for local governments that have run into difficulties with LGFV debt so far is debt restructuring. This will of course squeeze the returns that banks expected on their exposure to this sector and lower their profitability. As a result, some banks may need to raise capital to make up for any losses.

Meanwhile, the government is keeping the property development sector on life support through targeted assistance measures. These are being implemented alongside considerable supply-side improvements in order to help the functioning of the real estate market more generally and allow local governments to issue other ‘special’ bonds to pay outstanding liabilities more cheaply than LGFV debt. Consequently, while the real estate market is hardly thriving, massive failure has largely been avoided. Companies like Evergrande are being quietly absorbed or broken up rather than being allowed to fail spectacularly with the ensuing collateral damage that this would imply.

As a result, financing difficulties are likely to be spread out over multiple years – this limits the risk of a systemic crisis but suggests that an extended period of adjustment and possibly constrained credit extension as well as weaker economic growth looks likely.

ECB quantitative tightening risks brining back debt sustainability concerns

There seems to be a growing view within the European Central Bank (ECB) that in order to get inflation further under control, policy rate hikes might not be sufficient. In fact, the risk of worsening the current stagnation in the eurozone with additional rate hikes is high. In times of inverted yield curves, the ECB’s focus is likely to shift to non-interest rate tools again. Based on official comments since the September ECB meeting, an earlier end to reinvestments under the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) than the current “end of 2024” has become more likely.

The risk associated with an earlier end of the PEPP reinvestments is an unwarranted widening of spreads, particularly during a time when fiscal policies in the eurozone will turn more restrictive and the entire fiscal framework – the Stability and Growth Pact – is still subject to revisions. Consequently, an earlier unwinding of PEPP would return financial markets’ focus back to debt sustainability issues in the eurozone. The monetary union is clearly more solid and better prepared than in 2010 to weather a new sovereign debt crisis. However, as long as inflation remains above target, the ECB will not be able to perform the role of unconditional lender of last resort. Instead of whatever it takes, the ECB will only be able to offer its Transmission Protection Instrument. No single crisis ever repeats identically, but an earlier unwinding of the PEPP reinvestments clearly bears the potential to bring back debt sustainability tensions.

US commercial real estate remains a financial stability and economic risk

The plethora of risks to the US economy is highlighted by the wide range of views on where the Fed funds policy rate will end in 2024. On the positive side, we find that the Federal Reserve and a handful of other banks see little scope for any monetary policy easing in 2024. A tight labour market and a US consumer that has, so far, shown little inclination to slow the pace of spending could keep inflation higher for longer, especially if unions continue to extract inflation-busting wage agreements. This sets a benchmark for broader pay deals.

On the other end of the spectrum, there are several prominent banks that see interest rates being slashed through the coming year. Here, the sense is that, after the most rapid and aggressive series of interest rate increases for forty years and banks rapidly tightening their lending standards, something will eventually “break”. We are seeing delinquencies on credit cards and auto loans picking up rapidly, but most concerns centre on the commercial real estate sector. With around $1.8 trillion of commercial real estate debt needing to be re-financed over the next 18 months at a time when office occupancy and business travel remain down from pre-pandemic levels, there is a sense that owners could increasingly hand the keys over to the banks. Refurbishment and higher borrowing costs may mean that it simply isn’t worth holding onto the property, and with valuations coming under significant downward pressure, this could impact the balance sheet of banks.

Given that small and regional banks which account for around 70% of lending to CRE still remain stressed, such a situation could see confidence deteriorate with more deposit flight, thus creating instability in the financial system. Lending conditions would tighten across the economy, threatening to choke off credit flow to broad swathes of the economy. The Fed would inevitably respond with interest rate cuts likely being rapidly priced in by financial markets.

Content Disclaimer

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user’s means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here