Long-term Treasury yields have been far lower than short-term Treasury yields for a year, as the Fed pushed up its short-term policy rates, but the Treasury market has refused to play along, and long-term Treasury yields have been slow in following. But this phenomenon is now facing massive headwinds.

Markets are going to have to absorb a flood of Treasury bills (Treasury securities with maturities of one year or less) in the coming months, estimated at something close to $1 trillion, as the Treasury is trying to refill its depleted checking account, the Treasury General Account, while also covering higher outflows and lower tax receipts (we discussed this most recently here). This has been teased in a series of Treasury department announcements that keep getting worse.

The net new issuance will pull liquidity out of other markets and put upward pressure on short-term Treasury yields and on other interest rates, including for CDs, as more and more buyers need to be found to buy these bills, and higher yields will do that.

We knew that. And it’s happening. Investors in bills and CDs are finally getting some yield, after 15 years of getting screwed.

For example, today, the Treasury sold $162 billion in securities, of which $120 billion were Treasury bills with juicy yields:

- $58 billion in six-month bills at an investment yield of 5.45%

- $62 billion in three-month bills at an investment yield of 5.34%.

- $42 billion in two-year notes at a high yield of 4.67%, amid very strong demand. Longer-term yields are still far below short-term yields.

The Treasury department wants to refill the TGA account to where it reaches $600 billion by the end of September. Borrowing to refill it will have to cover a lot of spending, lower tax receipts, plus the extra portion needed to increase the cash balance.

By the end of May, before the flood of new issuance started, there were $4.0 trillion in Treasury bills outstanding, about 16.4% of total marketable Treasury securities ($24.3 trillion at the time).

With the flood of Treasury bills now being issued, their share will soon hit 20%, which is seen by the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee as the upper limit for the US to fund deficits at the least possible cost to taxpayers, according to JPMorgan Chase, cited by Bloomberg.

The Treasury will soon have to issue more longer-term debt (notes and bonds) by increasing the auction sizes, to keep the proportion of Treasury bills in its pile of total marketable securities from ballooning out of whack.

Sales of Treasury notes (2-10 years) and Treasury bonds (20 and 30 years) are expected to rise, starting in August, according to the head of US Rates Research at Barclays Capital, Anshul Pradhan, cited by Bloomberg. He predicts that the net rise in notes and bonds from August to year-end will be nearly $600 billion, and ramp up further in 2024, when about $1.7 trillion in notes and bonds would be added, nearly double this year’s expected additions.

To find buyers for this added debt, yields would have to rise. He added, “We believe the rates market is too complacent.”

At the same time, some big buyers are unloading:

- Foreign buyers shed $140 billion in holdings in April compared to a year earlier, according to the Treasury Department’s TIC data.

- US banks shed $210 billion in Treasury securities and $332 billion in government-backed MBS in May compared to a year ago, according to Federal Reserve data. They’re struggling with unrealized losses from holdings that they’d bought when yields were ultra-low.

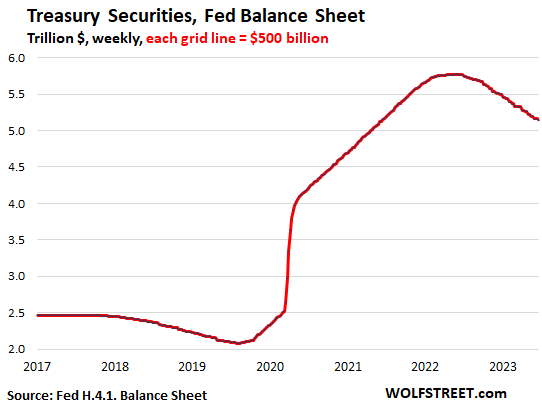

- The Fed has been unloading Treasury securities at a rate of $60 billion a month, month after month, as planned (its holdings of MBS are rolling off at a much slower pace):

It could result in a “demand vacuum” that would be resolved by higher yields for longer maturity securities, according to Bank of America, cited by Bloomberg. Yield solves all demand problems, and long-term yields have been much lower than shorter-term yields, with the 10-year Treasury currently at 3.71%

The higher long-term yields needed to attract enough buyers to sell the onslaught of notes and bonds would steepen the yield curve and push other long-term rates higher, such as mortgage rates and the rates companies would have to pay to sell new bonds.

This is of course precisely what the Fed wants to accomplish by hiking short-term policy rates and engaging in QT in order to throttle inflation back down. These policy measures have to translate into financial conditions – financial conditions need to tighten in order to get the magic done – but they remain amazingly loose. The market’s refusal to play along so far has made the Fed’s job a lot more difficult. But as long-term yields rise to deal with the flood of issuance of notes and bonds begins later this year, the Fed might finally get some help from the bond market.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Read the full article here