About the author: Desmond Lachman is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was previously a deputy director in the International Monetary Fund’s Policy Development and Review Department and the chief emerging market economic strategist at Salomon Smith Barney.

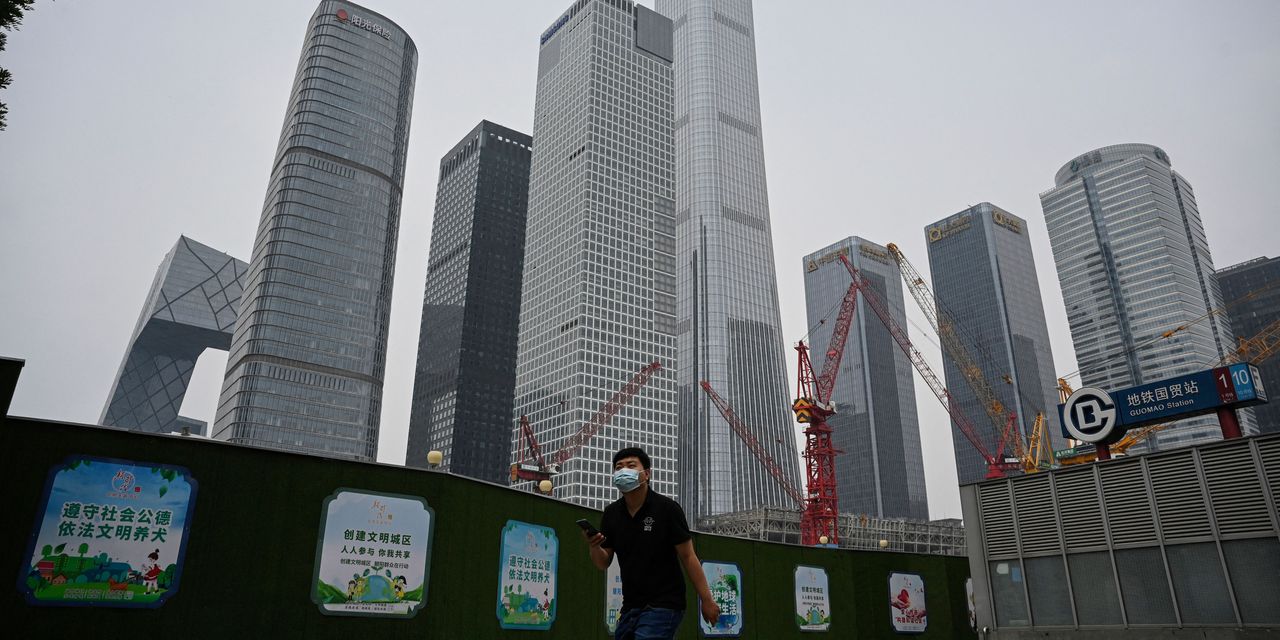

So much for the Chinese economic boom. Last year China ended a disastrous zero-Covid policy that had crippled its economy. A rush of growth was widely expected to follow. Instead of booming, five months after the ending of its Covid restrictions, the Chinese economic recovery is sputtering. That is due in no small measure to the bursting of its outsized housing and credit market bubbles.

The question now is whether China will experience a lost economic decade as Japan did in the 1990s following the bursting of its property and credit market bubble. We may be at the end of the period when China, the world’s second-largest economy, served as the world economy’s main growth engine and the main driver of international commodity prices.

At the start of this year, against the backdrop of dimming prospects for the inflation-ridden U.S. and European economies, the International Monetary Fund along with many market analysts projected that the reopening of the Chinese economy would provide much needed support to the global economy. Led by an anticipated sharp rebound in consumer spending, the IMF forecast that Chinese economic growth would pick-up from its multi-decade low of 3% last year to 5.2% percent this year.

Alas, this does not seem to be transpiring. A bundle of recent disappointing Chinese economic data, including retail sales, factory orders, and imports, all suggest that the Chinese government will have trouble meeting its 5% economic growth target. So too do indications that a number of major Chinese local governments are struggling to meet their debt obligations and that Chinese youth unemployment has risen to a worrying record 20.4%.

The apparent failure of the Chinese economy to regain its past rapid economic growth path following the ending of the Covid restrictions should have come as no surprise to those who had been paying attention to the bursting of the Chinese housing and credit market bubbles. This is especially the case considering that those bubbles exceeded the size of those that preceded Japan’s lost economic decade in the 1990s and that preceded the U.S. recession of 2007-2009.

Chinese non-public-sector credit has increased by more than a staggering 100% of gross domestic product since 2008, according to the Bank of International Settlements, since 2008. Meanwhile, housing prices in relation to incomes in a number of major Chinese cities increased to levels exceeding those in London and New York, a study by Harvard’s Kenneth Rogoff found.

Anyone doubting that the Chinese housing and credit market bubble has burst need only recall that last year Evergrande, along with 20 other Chinese property market developers, defaulted on its debt. They also might take note of the fact that Chinese housing prices have declined in each of the last 12 months and that a number of major local governments are now running into difficulties in repaying their debt as land sales have screeched to a halt.

This is all not to say that China is likely to experience a U.S.-style bust led by a housing and credit market collapse. Rather, it is to say that the Chinese government’s efforts to prop up the housing market and the ailing local governments will leave little credit available for the more productive sectors of its economy. That in turn threatens to usher in a lost Chinese economic decade a la Japan’s of the 1990s.

One silver lining of a likely lost Chinese economic decade is that we no longer need to worry that China will eat our economic lunch. As occurred with the supposed Japanese economic miracle in the 1980s before it, we will find that the Chinese economy had clay feet. Another silver lining of a secular Chinese economic slowdown is that we might get much needed inflation relief in the form of lower international commodity prices and reduced Chinese export prices. That might allow the Federal Reserve to let up on its newfound monetary policy religion.

Desmond Lachman is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. He was a deputy director in the International Monetary Fund’s Policy Development and Review Department and the chief emerging market economic strategist at Salomon Smith Barney.

Read the full article here